Slaughter sites and killing fields are a major money-maker in Cambodia, but is this right? Marissa Carruthers reports the dark side to them as the kingdom moves on from the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime

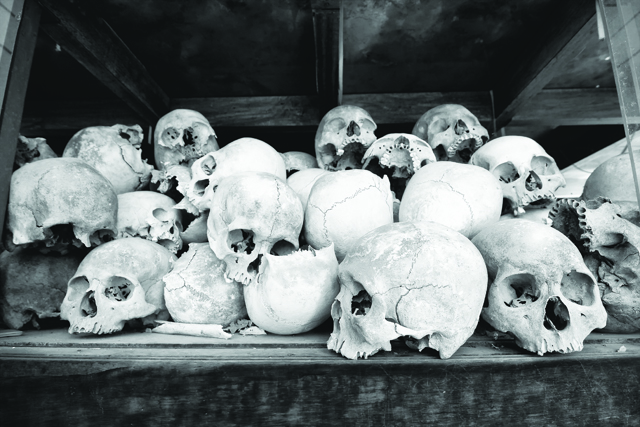

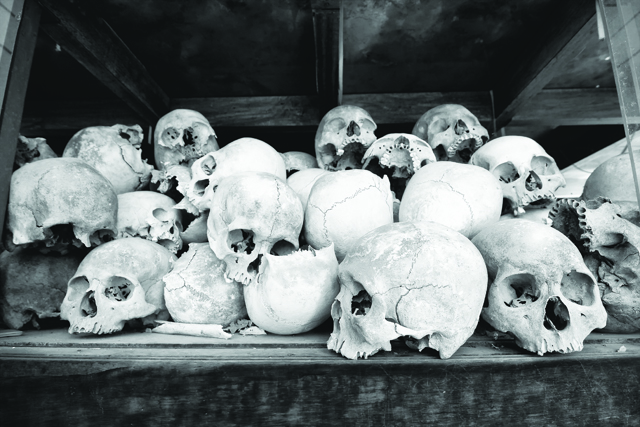

Skulls of torture victims resting in a stupa at the Killing Fields outside of Phnom Penh

As a country ravaged by decades of war, Cambodia is littered with former slaughter sites, killing fields and bitter memories for those who survived. While Angkor Wat remains the main tourist draw, the capital’s barbaric S-21 prison and nearby Choeung Ek – one of the largest killing fields – also top the list of attractions.

S-21 or Tuol Sleng – the political prison where an estimated 17,000 Cambodians were tortured to death or sent to be slaughtered at Choeung Ek between 1975 and 1979 – receives 500 visitors daily, with more than 800 a day venturing to the Killing Fields during high season.

And while most international tour operators omit it from their itineraries, many tourists seize the opportunity to include the shooting range in the popular Choeung Ek-S-21 trip. Here, large sums of money are paid to fire AK47s, rocket launchers and other ageing weapons.

Pierre-Andre Romano, general manager of EXO Cambodia, said: “This is definitely not tourism. It’s voyeurism. You can go and learn about the Khmer Rouge, then pretend to be one? That isn’t right.”

According to Elizabeth Becker, a war correspondent who covered Cambodia throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Cambodia’s genocide tourist attractions should not exist. In her book, Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism (2013), she accuses the country’s dark tourism industry of being exploitative and disrespectful to those who died, and those who survived.

It’s ‘education’

However, Kimhean Pich, CEO of Discover the Mekong, disagrees. He said these dubious attractions not only drive tourism but provide a way to educate the world, and Cambodians.

He said: “For local people, these are places to learn about our bitter history and to make sure we avoid repeating (the same) mistake in the future. For tourism, it is a unique product and attracts many visitors. Other countries can create similar events, temples and infrastructure, but they can’t make up a history like ours.”

But Romano argues it is time for Cambodia to “turn the page” and start promoting the country’s other unique products, such as the wealth of community projects, rare wildlife and rural living. He added Exo Travel includes the Killing Fields and S-21 on tours due to high demand.

He said: “Of course, these sites are necessary for the education of Cambodians and to help the country understand and move forward. But for tourism, no.”

As visitor numbers to genocide-related sites increase, reports of vandalism and disrespectful behaviour are on the rise. At Choeung Ek, visitors have been found collecting bones. Inappropriate selfies are often snapped in front of the blood-splattered torture tools at S-21 and graffiti sprawled across images of Pol Pot.

Last year, outrage erupted when Pokemon Go players stormed S-21 to capture characters. It resulted in the game being banned.

This is an issue Pich said needs to be tackled, with tour guides and agents having a role to play.

He said: “Before they visit the site, visitors need to be clearly informed about their behaviour. It is difficult for tourists to truly understand what our dark history means to us. Even some Cambodians have difficulty understanding, unless their family, relatives or they themselves experienced the regime. Guides and tour leaders must translate those memories to be understood well by tourists and ask for their respect.”

One organisation that is using tourism as a tool to educate and help the country heal is the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). It has spent the last few years working in the remote area of Anlong Veng, the final Khmer Rouge stronghold.

Home to 14 landmarks, including Pol Pot’s cremation site and home of infamous commander Ta Mok, the area is predominantly inhabited by former Khmer Rouge cadres, who are exiled from society.

Two years ago, DC-Cam opened Anlong Veng Peace Center, and has developed many of the sites, adding information for visitors. In July, it will start training local tour guides, and has encouraged former Khmer Rouge soldiers to share their experiences with visitors, many of whom are currently Cambodian students.

“Our main objective is to promote memory, justice and reconciliation,” said centre director Ly Sok-Kheang. “We believe this can be done through dialogue and education. If a visitor really wants to learn about the Khmer Rouge, Anlong Veng is the best place to start and it can be developed into an important historical and educational tourist site.”

Sinan Thourn, chairman of PATA Cambodia Chapter, agrees that dark tourism has a role to play in preserving the turbulent past. But it needs to evolve and the focus shift away from the macabre, such as the skulls and bones of Choeung Ek or the harrowing cells of S-21.

He said: “Why can’t we add cultural elements? Villages next to Choeung Ek can open (their homes to) homestays, or show what happens to Cambodian people when they die and put on Buddhist funeral ceremonies for visitors. We can’t forget Cambodia’s history but we can’t just keep bringing people to these settings.

“Often when foreigners think of Cambodia, they think of landmines, genocide and Pol Pot. There is much more than that and there needs to be more promotion of the alternatives to get rid of this bad image.”